Future IDs: Reframing the Narrative of Re-Entry

By Gregory Sale with Aaron Mercado, Dominique Bell, Luis Garcia, Jose Gonzalez, Ryan Lo, and Kirn Kim with Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC), Phoenix, AZ & Los Angeles, CA.

FROM: Art as Social Action: An Introduction to Principles and Practices of Teaching Social Practice Art, edited by Gregory Sholette, Chole Bass, and Social Practice Queens. New York, NY: Allworth Press, 2018.

“Listen, you don’t have a lot of time. I just want to show you something.” And I reached into my pocket and pulled out my old prison ID. He looked at it, and then I went in my other pocket and showed him this college ID. And I said, “This is the different side. That is the difference.” And [the Senator] responded, “Enough said.”

— Dominique Bell, project collaborator

Future IDs Art Workshop combined future planning, artmaking, and writing exercises for individuals with conviction histories. It was an essential component in a developing collaborative art project about individual stories of transformation and how, collectively, those stories can help reframe the narrative of re-entry.

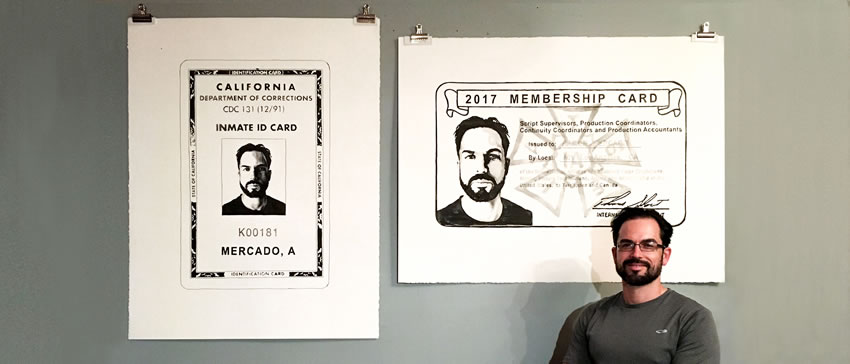

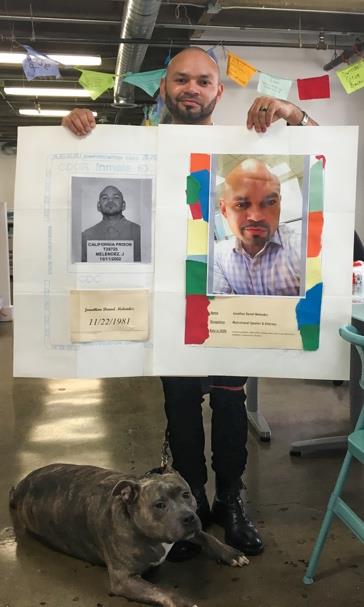

The workshop provided a structured environment for participants to engage in a creative process as individuals and as members of a community. The central idea was to juxtapose artistic re-creations of past or current inmate IDs with identification cards for future selves – perhaps for a dream job, a role in society, or a continuing role with family, such as father or mother. Participants were then asked to write a simple message to themselves and others about their intention for that future self.

This assignment was collaboratively designed with members of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC) – Aaron Mercado, Dominique Bell, Luis Garcia, Jose Gonzalez, Ryan Lo, and Kirn Kim. Founded by Hollywood producer Scott Budnick, ARC is a movement of system-involved members, community advocates, and allies committed to transforming the justice system. ARC members share their turnaround stories with elected officials to convince them that rehabilitation is possible, leading to laws for more humane sentencing for juveniles and restored budgets for prison college programs.

For two years, I have served as an ally and embedded artist with ARC. Future IDs was the first major project stemming from our partnership, adding a visual and cultural component to the individual growth and advocacy work that ARC and its members undertake.

Leading to the workshop, the conceptual framework of Future IDs was introduced at the ARC annual retreat, during project development sessions, and with an exhibition at the ARC offices. ARC members were shown what participants could expect and what to prepare beforehand. Throughout an eight-hour day, nineteen ARC members and four allies participated in this inaugural workshop. Five core participants helped co-facilitate, along with guest artists, a life coach, and a writer. The event was held at the ARC offices in downtown Los Angeles.

The Workshop: Learning Modules

Every child is asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” For many of us, we lost the opportunity to fulfill that childhood dream. But that doesn’t mean we still don’t have the desire to become something that redefines who we are. So I ask, what do you want to be when you grow up? What ID do you want to be carrying in the future?

— Kirn Kim, core project collaborator

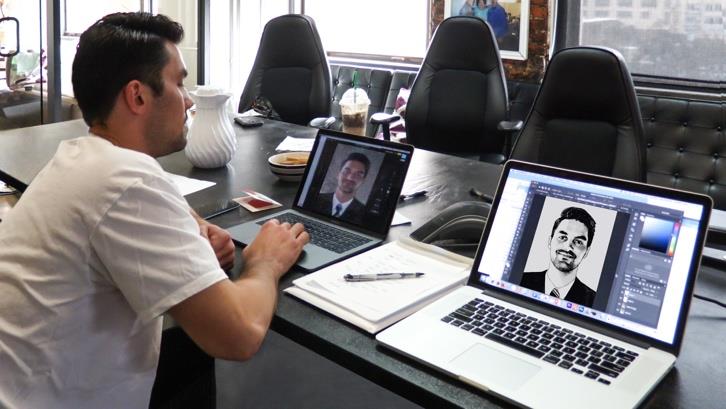

We began with introductions and a discussion with Sara Daleiden, social practice artist and co-director of The Bunny House. The core project collaborators explained our conceptual framework and how the individual components would form a successful overall project. We first studied public campaigns that dealt with mass incarceration, stigma, race, and inequity, and discussed the cultural scripts that accompany those who have been incarcerated. We expressly created an opportunity to consider visual components that correspond to incarceration in the public eye, as well as the cultural, social, and political impacts of those visual components. We noted that someone, somewhere, had designed the prison ID. We devoted time to engage a discussion on the power of that image and what it might mean to take ownership of it by making one’s own.

Later, we carried out a group exercise focused on creating context around images, considering a range of strategies that contemporary artists use to create portraits. Several ARC members who self-identified as artists led a discussion on how artistic production is valued differently inside prison culture than in the art world.

Future Planning

Writing a clear picture of your life goals will help you clarify your priorities and enable you to create strategies for realizing your dreams.

— Colleen Keegan, Strategic Planning Training, Creative Capital Foundation

The second module began with a listening session that worked in part as an icebreaker. We learned that the participants came from diverse life experiences. I then introduced an exercise I use with my university art students to help them uncover the center of their art practice: based in identifying early childhood passions and favorite play, we considered what was modeled at home or in life while growing up. Thirdly, we reviewed a Life Planning and Goal Setting Workbook that helps with setting short-term and long-term goals, their core values, and basic action plans.

Participants discussed the bravery required of formerly incarcerated persons to aspire to professions that some might consider impossible to achieve. Others, with expansive lists of possibilities for their future selves, focused on one revenue-earning job for purposes of this project. Some, whose future goals had not crystallized yet, but who planned to get job training or go to college, settled on making student IDs.

Artmaking

For the third module, participants were invited to draw, paint, collage, or reproduce their ID images, texts, and design elements in any artistic way of their choice. They were provided with four large sheets of multi-media paper on which simple outlines of generic identification cards had been previously drawn with architect blue-print pencil. Each sheet folded to fit into a 9” x 12” envelope, so it could be sent in and out of prison mailrooms, and easily transported on the outside.

Before drawing, we discussed the structure of identification cards and the types of information that are regularly included: images, job titles, company names, icons, logos, and bar codes. We provided a book of examples from various professional fields. Participants researched online; those who could not find specific resonant examples were encouraged to invent their new IDs creatively. Visual artists Rojelio Cabral, Aaron Mercado, and I were present to assist participants with technical and conceptual aspects. Rather than teaching collage, drawing, or painting skills, these artists led conversations about learning how to think and solve problems creatively, as well as on how to later express that process. All participants honed their conceptual understanding and set course for their individual projects.

Writing

The fourth module, led by Matthew Mizel, framed the question posed to all participants: to write a simple message to themselves and others about their intentions for their future. Participants were asked to include that job title or life role in their central personal messages. Mizel grounded the exercise by asking them to provide a basic dictionary definition of that job title or role. He then continued with a series of prompts that invited participants to envision themselves in various scenarios as that future self, talking and engaging with others. One project collaborator wrote: “Pray for me to be the father I can be,” and another, “Learning from my past has taught me how to be a teacher.”

Wrap Up

Participants were encouraged to continue working on their individual artworks after the workshop ended. They were informed of follow-up opportunities for support and feedback, for contributing from their individual artistic and writing output to the overall project, and encouraged to make some for themselves. Over the next year, core project participants and I will collect finished artwork, building several events, including an exhibition with public programs.

What made this project real for me was when I read “Pray for me to be the father I can be.” As a future intention, that statement humanizes us. A lot of us grew up without a father. It was at that moment that I realized how essential this project could be to our community and to our growth and to the growth of ARC as a whole.

— Jose Gonzalez, core project participant

Participants noted that the day provided them a chance to reflect on the future in ways they had not anticipated, challenging them and giving them strategies to connect with themselves at a deeper level. Even without regard to the outreach potential of the finished artworks, they found the artmaking process affirming and validating. They appreciated the possibilities for experimentation that art opened up for them. We all made suggestions for refining and systematizing the workshop, to later present it in a range of contexts, both inside prisons and in other community settings. Some participants offered to help produce a videotape of the workshop content to program on closed circuit TV channels inside prisons. Others proposed extending the workshop process over several sessions to have greater impact.

At the same time, they acknowledged the difficulty of regularly attending training sessions, given the challenges and limitations they face in their day-to-day lives. They identified a kind of “nomadic fickleness” that accompanies post-incarceration life. We are now developing a more elaborate workshop to unfold over a three-week period, taking these issues into consideration.

After the workshop, we feel confident about our goal of generating a dynamic visualization of individual transformations in a collective art project. The group discussion confirmed our sense that project participants creating images and representations of their lived experiences will add an essential cultural component to their personal and professional work to facilitate successful re-entry.

Just wanted to share how grateful I am to have participated in the workshop. Little bit of lecture, some sharing, and practical application with the beginning of our individual projects. The initial life story exercise was a great ice breaker. Also, bringing up old memories did allow for dormant feelings to emerge from my past experiences. The process really allowed us to be vulnerable. I recognized how much I still battle with my own self-perceptions, and how I can underestimate my creativity. We are all creative in our own way!

— Luis Garcia, core project collaborator

As an educational and teaching organization, ARC has become very effective at communicating its messages to elected officials. This project is designed to expand ARC’s capacity to communicate the value of criminal justice reform to the general public and thereby generate the critical community support necessary to advance justice reform. Society does not always think of people in prison as having a future. By creating connections to bring forth the humanity of those incarcerated, the project will interject this connectivity into the collective cultural space, thereby raising public awareness and changing social perceptions.

The project has received support in part from Creative Capital Foundation, SPArt (social practice art), and the Herberger Institute of Design and the Arts, Arizona State University.

Also available as a PDF, here